Pea Island Crew, Richard Etheridge on the left.

As a boy, on travels with my father down the Hatteras Island highway today known as NC Highway 12, we would pass the abandoned Coast Guard life-saving station at Pea Island, on the northern tip of Hatteras. The Coast Guard is the successor of the U.S. Life-Saving Service. Being a Coast Guardsman, Dad would note that an all African-American unit crewed the station and how unique that was in the service. The facility is no longer present on the beach as time and rising sea levels have forced the structure's relocation.

Pea Island Becomes a Segregated Station

The story of how the station became the only racially segregated unit in the Coast Guard begins with one man, Richard Etheridge. Born into slavery on January 16, 1842, Etheridge was raised on Roanoke Island. By 1862, the occupying Union Army on the island had freed the enslaved inhabitants. The Federal forces began recruiting from the African-American residents. Hence Etheridge decided to enlist in the Second North Carolina Colored Volunteers and was appointed as a sergeant in Company F, serving in Virginia and Maryland, eventually mustering out in Texas. After the Civil War's end, Etheridge returned to Roanoke Island, afterward working as a "surfman" in the newly formed Life-Saving Service. He served on several integrated or "checkerboard" crews, first at Oregon Inlet in 1875, then Bodie Island in 1879. Tragically in November of that same year, the mixed-race unit of nearby Pea Island Station mishandled a rescue effort with a significant number of casualties among the shipwrecked crew. The Revenue Cutter Service investigated the situation and reassigned the keeper to another post at a different station. Because of his military leadership experience and superior boatmanship, Richard Etheridge was appointed as keeper of the station. The officer who advised his appointment, First Lieutenant Charles F. Shoemaker, stated that Etheridge was "one of the best surfmen on this part of the coast of North Carolina." After Etheridge was appointed, the white surfmen were transferred to other stations. To fill the positions, Etheridge was directed to recruit local African-American men. Keeper Etheridge immediately developed stringent drills that enabled his team to excel in all life-saving tasks. Pea Island Station thus earned the reputation of "one of the tautest on the Carolina Coast."

During the Antebellum Period, the port of Washington, N.C. was a major shipbuilding center for North Carolina. But did you know that one of Washington’s most successful shipbuilders was a “freedman,” a former slave who had been granted his liberty by his former owner and rose to be one of Washington’s most successful businessmen? His name was Hull Anderson. Anderson’s story is one of a thriving entrepreneur but ends in the eventual abandonment of his home and business in Washington, N.C. for life in a strange country. But why would he desert Washington and take his chances in a foreign land?

During the Antebellum Period, the port of Washington, N.C. was a major shipbuilding center for North Carolina. But did you know that one of Washington’s most successful shipbuilders was a “freedman,” a former slave who had been granted his liberty by his former owner and rose to be one of Washington’s most successful businessmen? His name was Hull Anderson. Anderson’s story is one of a thriving entrepreneur but ends in the eventual abandonment of his home and business in Washington, N.C. for life in a strange country. But why would he desert Washington and take his chances in a foreign land?

Read more: Hull Anderson: Free Black Shipbuilder of Washington

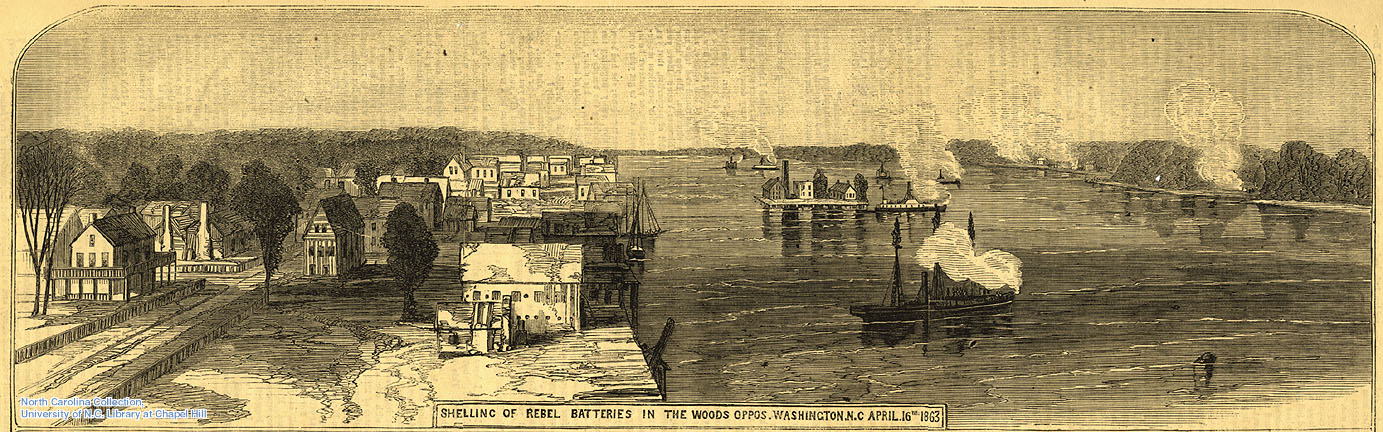

The time was spring of 1864. Union forces had occupied Washington for over two years. During that period, they were successful in holding off two attempts by Confederates to retake the town. Washington at the time was very different from bustling Washington prior to the war. It had established itself as a major sea and river port serving as the hub for the exchange of crops grown on the farms and plantations lining the Tar River and the goods manufactured in the Northeast U.S. as well as the sugar and molasses produced on the islands in the Caribbean. But after two years of occupation, commerce was suffering and many of the white population had fled town. The 1860 census showed the number of occupants in Washington to be around 1,600 with roughly 45% listed as white, 45% listed as slaves, and 10% listed as free men of color. But by 1864, the number of white occupants had dwindled to less than 500. However, as a result of a large number of Union troops and the influx of former slaves seeking refuge, the overall population had swelled.

The original show boat of the Southeast, the James Adams Floating Theater, was the first and only travelling boat to bring live theater annually to ports between Baltimore and Savannah, and it continued to do so between 1914 and 1941. Edna Ferber wrote her 1926 novel “Show Boat” after visiting the James Adams Theater while it was docked in Bath, launching the “show boat phenomena” into American culture. She is believed to have traveled on the James Adams from Bath to Belhaven in April 1925, and to have first met it in Washington in late 1924, after the season had closed. Ferber’s novel, inspired in part by the James Adams, led to the 1927 “Show Boat” musical and its song “Old Man River,” and later the 1929 “Show Boat” motion picture and its 1936 and 1951 remakes.

The original show boat of the Southeast, the James Adams Floating Theater, was the first and only travelling boat to bring live theater annually to ports between Baltimore and Savannah, and it continued to do so between 1914 and 1941. Edna Ferber wrote her 1926 novel “Show Boat” after visiting the James Adams Theater while it was docked in Bath, launching the “show boat phenomena” into American culture. She is believed to have traveled on the James Adams from Bath to Belhaven in April 1925, and to have first met it in Washington in late 1924, after the season had closed. Ferber’s novel, inspired in part by the James Adams, led to the 1927 “Show Boat” musical and its song “Old Man River,” and later the 1929 “Show Boat” motion picture and its 1936 and 1951 remakes.

Although Ferber’s story was about a boat named “Cotton Blossom” on the Mississippi River, and was based in part on Midwestern show boats, details in the novel undoubtedly reflect the James Adams Floating Theater, which was built in Washington. James Adams was born in 1873 in Ohio. He and his wife, Gertie, married young in Michigan and, bored with their jobs in a sawmill and a store, trained as circus aerialists. Adams’ first business venture in his early twenties was running a traveling “medicine show” selling “patent” cure-alls and potions.

Page 1 of 2